This Analysis on the Emergence of Clickbait Will Blow You Away

Companies like Facebook and Google aren’t merely providing a free online service - they’re competing for your attention because they need it to thrive in today’s economy. Your interactions on these platforms generate invaluable data without which the machine intelligence that makes them so intuitive and personalized would fail to exist. By making their services free to maximize their user base, many of these companies adopt business models that are dependent on the usage of their services, such as data collection and advertising. This is where our attention economy comes in, a theory widely discussed in the fields of psychology, advertising, and economics.

Economist and Nobel Prize winner Herbert Simon was perhaps the first to discuss this concept when he wrote,

In an information-rich world, the wealth of information means a dearth of something else: a scarcity of whatever it is that information consumes. What information consumes is rather obvious: it consumes the attention of its recipients.

In other words, as online content becomes increasingly abundant and accessible, our attention becomes the limiting factor to which content is consumed and the businesses that understand this are the ones that end up winning. So to compete in today’s complex and dynamic online landscape, it is vital for companies to capitalize on their consumers’ attention economy.

2 Things You Didn’t Know About Clickbait

What does this have to do with clickbait, you ask? Clickbait is the attempt to capitalize on your attention in the world of digital journalism, typically through headlines that promise content beyond an article’s true content. Some instead define clickbait as vapid listicles and mediocre content that simply shouldn’t exist on the Internet. Regardless of the definition, one thing is clear - clickbait is engineered to grab your attention. This is typically done through two methods which I will briefly discuss - manufacturing emotion, and leveraging our laziness.

In a paper called Breaking the News: First Impressions Matter on Online News (Reis et al., 2015), researchers found that the polarity of headlines (regardless of whether the emotion is positive or negative) had a strong influence on how many clicks it received. In another paper called Deep Feelings: A Massive Cross-Lingual Study on the Relation between Emotions and Virality (Guerini & Staiano, 2015), researchers published a comprehensive investigation on the relationship between the virality of news articles and the emotions that they evoke in the reader. They claim that virality is linked to particular configurations of valence (how positive or negative the emotion is), arousal (how strong the emotion is) and dominance (the level of control a person has over the emotion). Both of these studies show that by constructing the right headlines, editors can influence us to engage with the content by manufacturing a certain emotion.

In a way, clickbait is feeding our brain what it wants. Cognitive psychology has found that our brain prefers information that is spatially organized. Listicles with headlines such as the one for this section of the blog post often make use of numbers which hint at what the reader should expect when reading the article. Such headlines take the guesswork out of reading the news and eliminate the paradox of choice. According to psychologist Barry Schwartz,

Choice has made us not freer but more paralyzed, not happier but more dissatisfied.

Clickbait takes advantage of exactly this to grab our attention and encourage us to engage with the content.

I Analyzed 451,823 Headlines, and What Happens Next Will Leave You In Awe

To understand the emergence of clickbait in digital journalism, I decided to analyze ten years of headlines from The New York Times, a reputable newspaper with “worldwide influence and readership”. By using natural language processing techniques to analyze headlines and machine learning to construct a predictive model that can predict its ‘clickbaitiness’, we can get a sense of how headlines have changed over the past decade.

To train my model, I decided to adopt the approach used in the paper titled Stop Clickbait: Detecting and Preventing Clickbaits in Online News Media (Chakraborty, Paranjape, Kakarla & Ganguly, 2016). The work attempts to build a model that can detect the presence of clickbait in media sites, and warn the user of its presence. The data used consists of 16,000 headlines that are tagged according to whether they can be considered as clickbait. The clickbait corpus consists of headlines from BuzzFeed, Upworthy, ViralNova, Thatscoop, Scoopwhoop, and ViralStories. Examples of headlines from this corpus include

17 Places All Music Lovers Should Go In London

Ed Sheeran Has Revealed His Very Good Reason For Becoming A Musician

We Rode Hoverboards Around New York City And Here’s What Happened

The non-clickbait corpus consists of headlines from WikiNews, The New York Times, The Hindu, and The Guardian. Examples of headlines from this corpus include

Gas prices surge in Northeast US

No-fly zone demanded by Syrian protesters

Brazil wins FIFA Confederations Cup final, defeats USA 3–2

After reading in these headlines, I used a Bag of Words approach with a Naive Bayes classifier to train a model that could predict if a new headline was clickbait. If you’re unfamiliar with these terms, I’d strongly recommend reading Naive Bayes and Text Classification by Sebastian Raschka, which has a great overview of the methodology and why it works.

To build the NYT headlines dataset, I used The New York Times Archive API, which provides data on NYT articles since 1851. Using this to retrieve headlines from February 2008 to February 2018 (inclusive), I constructed a dataset made up of a decade worth of headlines. To distinguish between different types of content such as news articles, blog posts and media, the API has an attribute called type_of_material. To ensure that only news article headlines are being analyzed, the data was constrained to results that had a type_of_material of News. The data pulled from the API contained the following attributes for each headline:

main_headline: the official headline for the article

print_headline: the headline used for the print version of that article

pub_date: the date that the article was published on

section_name: the section of the newspaper that the headline is in

subsection_name: the subsection of the newspaper that the headline is in

word_count: total number of words in the article

This data gives us the ability to explore some interesting questions.

1) What proportion of headlines are clickbait, and how does that proportion vary over time?

2) How does the sentiment of headlines change over time? How much does their polarity vary?

3) Do the clickbait headlines have a common trend with regards to the section they are in or the word count of their articles?

4) How do the clickbait headlines differ from their corresponding print versions?

I Tried to Answer Some of Those Questions and You Won’t Believe What I Found

Before starting to answer any of the questions I posed above, I did some exploratory data analysis to verify the type of headlines that were being identified as clickbait.

On sorting the headlines by their probability of being clickbait as determined by the model in descending order, we see the same trends that we discussed earlier. The top clickbait headlines include phrases like what you didn’t know about …, here’s what happens when…, and x things to do …, which definitely look like clickbait.

Similarly, when we sort the headlines by their probability of being clickbait in ascending order, we should expect to see headlines that are not clickbait. The headlines above are very clearly not clickbait.

Proportion of Clickbait Headlines

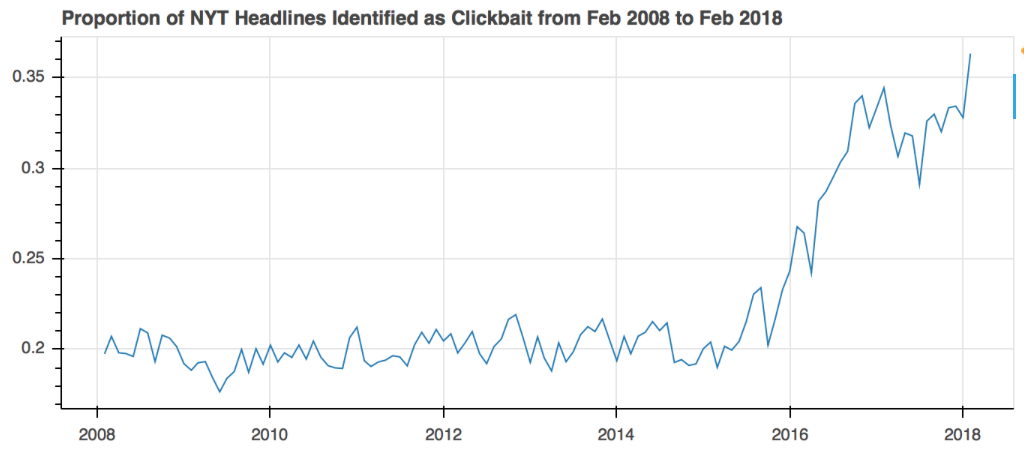

Now that we’ve convinced ourselves that the clickbait detection model is working, we can begin to answer the questions posed earlier and visualize some of the trends in clickbait headlines over time. Let’s begin with the most obvious question - how has the number of clickbait articles changed over time? Since the total number of articles each month varies, perhaps a more accurate measure is the proportion of articles each month that have been flagged as clickbait.

This result is very interesting for several reasons. First, that there is a very clear upward trend, meaning that the NYT has significantly increased the production of articles that have clickbait-like headlines over the past ten years. Second, that for some reason, the proportion stays consistent for nearly 7 years from Feb 2008 to Feb 2015, after which it rapidly increases over the next 3 years. It is interesting to consider the cause of this recent spike. Could this perhaps be due to a change in editing standards? Or a rise in clickbait journalism, reflective in general of the paradigm shift in digital journalism? Without any knowledge of any concrete changes made to the editorial process within NYT, one can only hypothesize.

Polarity of Clickbait Headlines

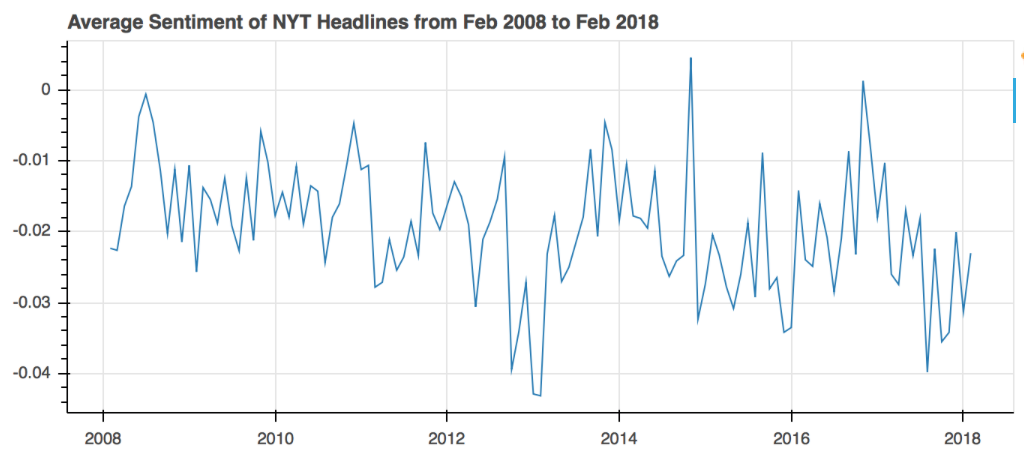

If the proportion of clickbait headlines has increased over the past ten years, should we also then expect to see an increase the polarity of these headlines? After all, as discussed earlier, clickbait works by leveraging on our emotions to encourage us to engage with the content. To answer this next question, I used the Valence Aware Dictionary and sEntiment Reasoner (VADER) tool within a popular natural language processing library called Natural Language Toolkit (NLTK). VADER is a sentiment analysis tool that determines the sentiment of some input text, i.e. whether it is positive, negative, or neutral. By running all the headlines through this tool, I then determined the sentiment of these headlines, visualized below over time.

Unlike the previous plot, this one doesn’t seem to have any clear trends that stand out. In general the trend seems rather random, with the exception of the global maximum (in Nov 2014) and minimum (in Feb 2013) which seem to deviate from the mean to the greatest extent. What is interesting here, however, is that the overall mean seems to be negative, meaning that the average headline has a negative sentiment. Not surprising, because it is probably more common to see stories about negative events more than positive events in the news. It is also possible that headlines for negative events tend to use words that have a higher absolute value than the words in positive headlines (i.e the negative words are more strongly negative than how positive the positive words are).

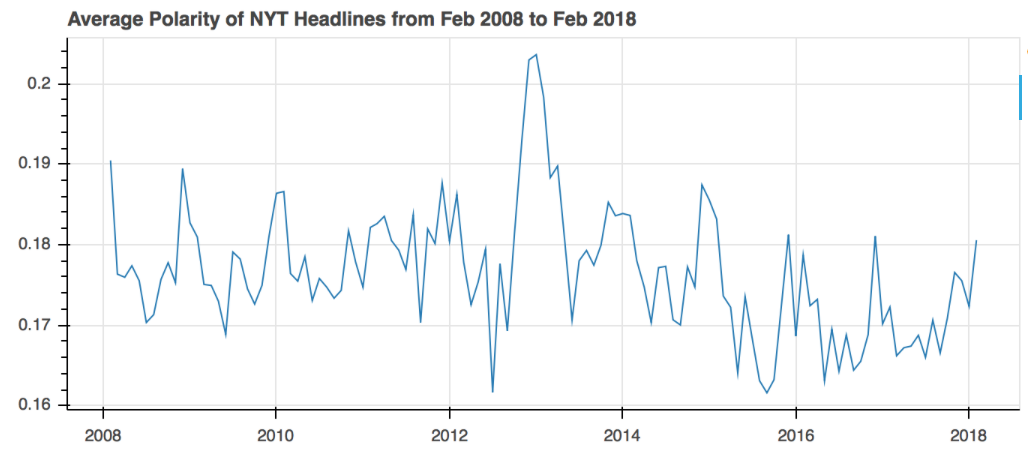

What about polarity? Since VADER gives us information about how neutral the headlines are, we can use its complement to understand how polar they are.

Again, no surprising trends here, other than the fact that there seems to be an abnormally high polarity in Jan 2013. But the seemingly random trend in polarity still doesn’t corraborate with the rise in clickbait headlines. One reason for this could be that clickbait headlines that were identified were flagged because of their format (such as 7 Things You Didn’t Know About … rather than their polarity. Another reason could be that since VADER is trained on social media text, testing on headline textual data will not yield the best results. Perhaps a better methodology to determine the trend in polarity would to obtain a dataset of headlines tagged with sentiment, and to train a predictive model on that dataset. However, I could not find one that currently exists, nor had the resources to construct one for the purposes of this project.

Category of Clickbait Headlines

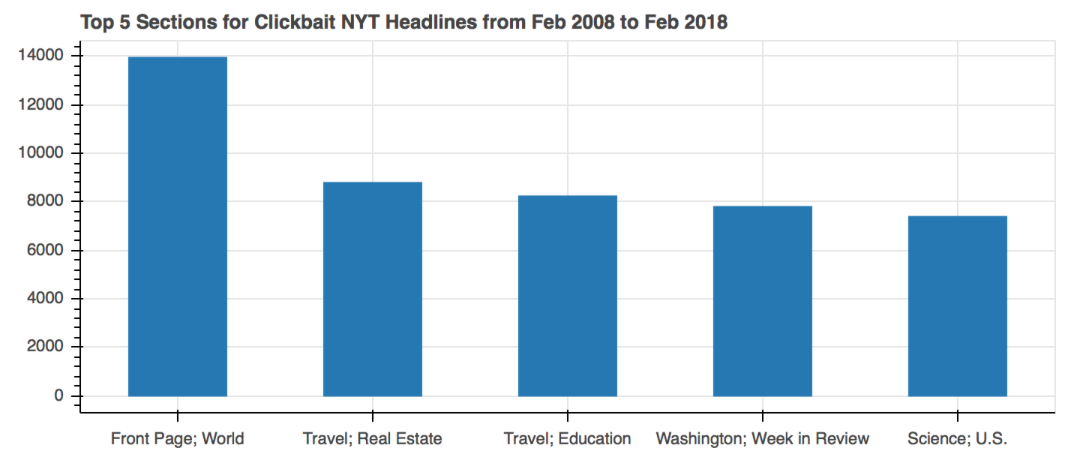

We can also look at which section of the news the clickbait headlines tend to appear in.

From the results, it looks like that the front page of the world news has the highest number of clickbait headlines, which is not surprising. Clickbait headlines are engineered to catch our attention, and if they’re on the front page, we’re more likely to engage with other content as well. Another top section is travel, which seems like the likely candidate for listicles such as 7 Places to Visit Before You Die, something you’d definitely be tempted to click on if you’re interested in traveling.

Medium of Clickbait Headlines

Another question I posed earlier was whether print headlines differed from their web counterparts. Turns out, there are in fact 43,714 headlines that are flagged as clickbait that differ in the way their headlines are present in the different mediums. That’s nearly 44% of the clickbait headlines. Here’s three of them.

Web: 6 Things to Do With Your Kids in NYC This Weekend

Print: For Children

Web: 9 Things Every Skier Should Know This Winter

Print: What’s New, On and Off the Mountain

Web: Here Is What Happens When You Cast Lindsay Lohan in Your Movie

Print: The Mistfits

And there are plenty more of such examples, where the print version is the more ‘tamed’ version of the web headline. The most common victim of this conversion seems to be the listicle - perhaps they simply don’t tend to work as well in print, but instead get much higher engagement on the web.

Characteristics of Clickbait Articles

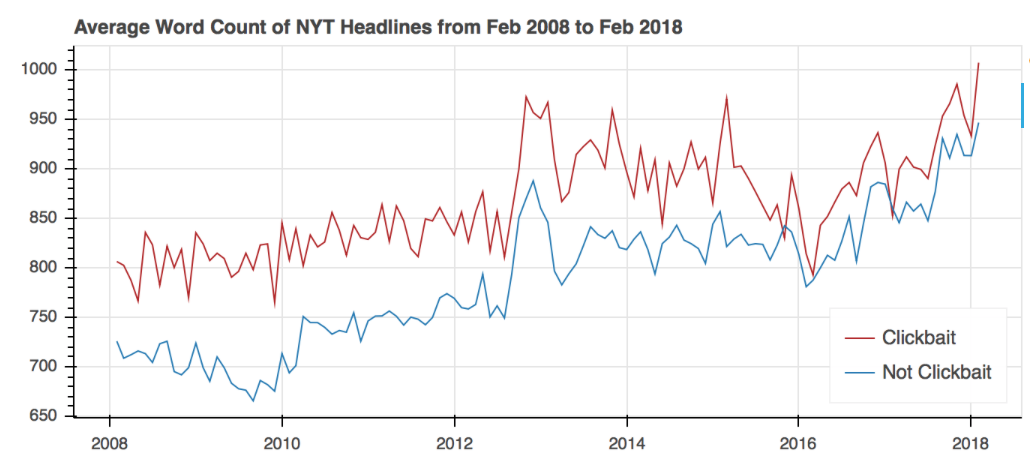

Now that we’ve looked at the headlines that get flagged by the clickbait detection model, the next logical step is to dig deeper into the articles to understand how they differ between those that are associated with headlines that are clickbait, and those associated with headlines that are not. One of the properties returned to us by the NYT API is the word count of the articles.

The trend for the clickbait articles is shown in red, while the trend for non-clickbait articles is in blue. While both the trends are generally similar, it is interesting to note that the clickbait articles are consistently longer on average than the non-clickbait articles over the past ten years. Clickbait is known to promise content of a higher quality than what the headlines seem to suggest, so is this trend indicative that NYT articles actually fulfill this promise? But then again, greater quantity does not always equate to greater quality, so it is possible that this promise is still not met. Regardless, it is surprising to note that clickbait headlines consistently lead to longer articles. Further analysis such as topic modeling or sentiment analysis on the text in the corresponding articles might be interesting to pursue.

This Article Reveals Why It’s Time to Rethink Digital Journalism

The motivation for this project was to do a preliminary study to understand how clickbait has emerged in our society in the past ten years, and the purpose of focusing on The New York Times was to show that it exists even in reputable and acclaimed news sources. To keep up with today’s highly dynamic and fast-paced tapping and swiping attention economy, it seems that simply having quality content is not merely enough. In order to drive user engagement and advertising revenue, it is perhaps inevitable that one must turn to methods that grab the attention of users and capture audiences by leveraging on our cognitive psychology and manufacturing emotion. Even for the most reputable sources in digital journalism, the existence of clickbait seems necessary, more so now than ever before.

How do we then maintain and improve the quality of online news content without using ‘underhand’ cognitive techniques to draw users, and instead actually provide unique value?

Maybe it is time to rethink digital journalism. Technologies such as virtual reality and augmented reality have finally evolved to a stage where it is not completely infeasible to create and distribute content. News publishing platforms such as Apple News are also making it possible for publishers to “craft beautiful editorial layouts” and use “fun interactions like animations to make stories spring to life”. Efforts such as these seem to be a step in the right direction. A direction in which users can be engaged without any compromise on the quality of the content being provided to them, in which the content is instead enhanced by the medium that serves it.